At Polish site, Ukrainians train to fly drones for rescue missions and targeting Russians

Yurii Shevchenko, a pilot with the Ukrainian Emergency Service, examines a Lemur drone at a training workshop organized by Brinc, a Seattle-based drone maker. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)

KUJAWY-POMERANIA PROVINCE, Poland — Olexi Kroshchenko, a clean-cut Ukrainian helicopter pilot, stood elbow-to-elbow with Chase Bailey, a bearded Las Vegas hipster, and learned how to fly drones in war zones.

Within days, Kroshchenko hoped, some of the 10 specialized quadcopters donated by an American manufacturer would be angling into the treacherous gaps of bombed-out apartments and high-rises, giving Ukrainian rescuers a better chance to reach victims.

“A little more throttle,” said Bailey, gently touching the joystick controller. “Watch the screen, not the drone.”

“Da, yes,” said Kroshchenko, 25, as he mastered the subtle pitch and yaw of a device designed — with laser guidance, night-vision and a concrete-penetrating signal — to operate in the kind of grisly rubble being created daily by Russian missiles and shells.

Nearby, two others — Ukrainian military officers who had traveled secretly into Poland — were practicing another wartime application: using the drones to soar above ridgelines and buildings to peer down at enemy forces and feed targeting locations to artillery units and reconnaissance information to commanders.

Exploding ‘kamikaze’ drones are ushering in a new era of warfare in Ukraine

They were rehearsing these new skills amid the sheds and garages outside a public safety facility in northern Poland, where the military officers and 10 others from the Ukrainian Emergency Service had come to meet a team from Brinc, a Seattle-based drone maker. Polish officials asked that the exact location of the training not be identified because of security concerns.

Chase Bailey, a drone pilot and trainer for Brinc, explains how to use the Lemur drone to Ukrainian pilots. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)

Chase Bailey, a drone pilot and trainer for Brinc, explains how to use the Lemur drone to Ukrainian pilots. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)

The pilots hope to use the drones to reach victims in buildings damaged during the conflict. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)

The pilots hope to use the drones to reach victims in buildings damaged during the conflict. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)

The Ukrainians now hoped the aircraft would make a difference in the growing hellscapes of Kharkiv, Kherson and Dnipro, Ukrainian cities where a lack of equipment and relentless attacks have made rescues difficult and perilous.

“There are many destroyed buildings and the conditions are too dangerous,” said Yan Koshman, a rescue official from an area near the Ukrainian city of Chernihiv who was waiting his turn at the controls. “This drone can go where we can’t.”

This two-day training and $150,000 worth of drones and supplies are part of the rapidly expanding transfer of technology, expertise and provisions to Ukraine from foreign companies and volunteers. Across Poland and other European neighbors, pop-up teams are finding ways to funnel critical resources across the border, from retrofitted vehicles and body armor to specialized orthopedic equipment and medicines.

The drone training was arranged with help from the Ukraine Freedom Alliance, a newly created nonprofit looking to bring some efficiency to the pell-mell rush of supplies and expertise toward the war zone.

After some basics, the training progressed to more challenging maneuvers. Bailey and the other instructors showed how the drone, called a Lemur, could push open a blocked door, enter confined spaces, flip over and fly if it was knocked on its back.

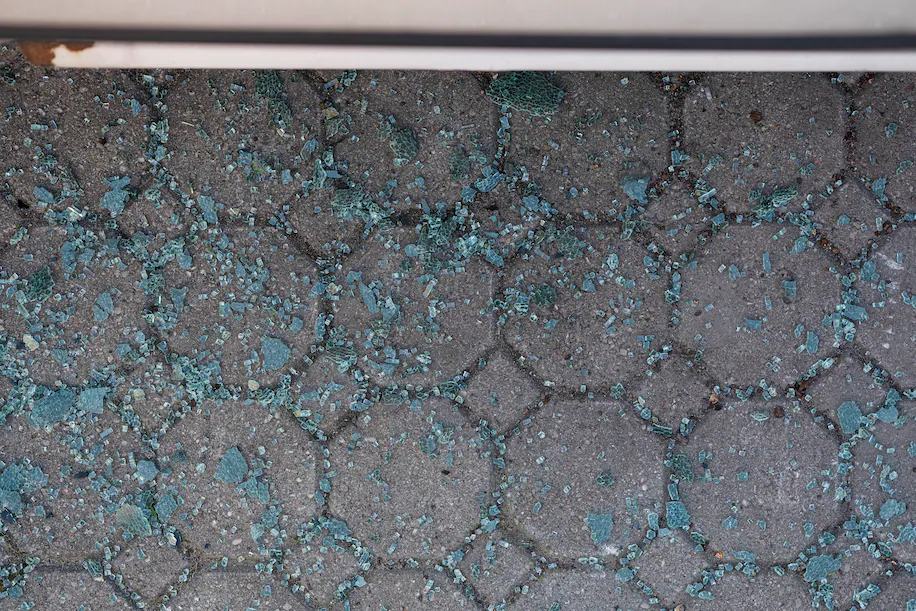

“That is mind-blowing,” Kroshchenko said after Bailey intentionally punched the drone through the side window of a derelict hatchback. After the craft was steered twice into the car, the glass gave way in a glistening shower of shards.

The Brinc pilot shows how the drone can crack the windows of a car. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)

The Brinc pilot shows how the drone can crack the windows of a car. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)

The shattered glass landed on the side of the car. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)

The shattered glass landed on the side of the car. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)

The drone emerges from the other side of the car. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)

The drone emerges from the other side of the car. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)

Blake Resnick, the 22-year-old founder of Brinc, watched with approval as the Ukrainians went through their paces. “Pretty impressive for so little flying time,” he said as two of the drones did figure eights. “They are really motivated.”

On one side of the training site, the two Ukrainian military officers worked at hovering the drone at higher altitudes. Drones are already used by both sides in the war to locate enemy forces and relay targeting data back to artillery batteries. While the tiny aircraft are difficult to shoot down, their signals can be jammed and even traced back to the drone operator, who would then be the new target.

“If they find us, they shoot at us,” said one of the men, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of security concerns. “We have had to pack up and run.”

The Lemur, which navigates by laser-based lidar rather than satellite-based GPS, is less hackable.

Ukraine’s Mykolaiv has held off Russian forces. Bodies are piling up anyway.

Resnick, as a teenager, developed the Lemur after the 2017 Mandalay Bay shooting that killed 60 people in his native Las Vegas. He said he envisioned a device that SWAT teams could use to reach shooters and hostages in hazardous settings. The drone’s communications system allow users to negotiate with bad guys or reassure victims.

Lemur quadcopters had proved useful to rescuers at last year’s collapse of the Champlain Towers condominium building in Surfside, Fla. Rescuers flew the devices into the wreckage while there was still the risk that a second adjoining tower could collapse, according to Byron Evetts, a structural specialist who worked at that disaster scene. The drone allowed them to monitor individual cracks for any sign of shifting or movement.

And in combat situations, the drone’s range can be invaluable by letting the operator stay thousands of feet away.

A pilot from the Ukrainian Emergency Service tests the Lemur drone. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)

The pilots will have access to $150,000 worth of technology. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)

As the drones zipped past through Poland’s afternoon sky, Phil Anderson, the Washington-based consultant who started the Ukraine Freedom Alliance, fielded calls about other supply efforts.

“Well, I can’t thank you enough,” he said, finishing a conversation with an executive who was willing to lend a Falcon 900 jet to ferry more than 5,000 pounds of combat trauma aid and other supplies collected by the Special Forces community around Fort Bragg, N.C., and other places.

Inside the transfer of foreign military equipment to Ukrainian soldiers

Once materials get to Poland, the challenge is finding Ukrainians to take custody. On the morning drive from the Polish capital of Warsaw, Anderson had taken a call from a medical group that had made it into Ukraine with a team of doctors, equipment and an ambulance but nowhere to deploy.

Anderson turned to his main Ukrainian partner, a well-connected former military pilot who operates his own air transport company. After an hour, the man approached Anderson with good news. He had called a member of the Ukrainian parliament, who had in turned contacted the minister of health.

After 15 hours of practice, the drone trainers began packing up their aircraft. The drones were on their way to Warsaw, and the former military pilot would get them into Ukraine.

“This is one of the most black-and-white wars I can remember,” Resnick said. “I think it’s just about a moral obligation to support them.”

One of the Lemur drones provided by Brinc is tested by the pilots from the Ukrainian Emergency Service. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)

One of the Lemur drones provided by Brinc is tested by the pilots from the Ukrainian Emergency Service. (Karolina Jonderko for The Washington Post)